Can the EU's Long Term Vision and the Rural Pact become a reality in the post-2027 Rural Development Policy?

- Edina Ocsko

- Sep 5, 2024

- 14 min read

Food for thought in response to the questions set by the LTVRA Report

No more business as usual[1]

Rural areas are confronted with significant challenges, such as depopulation and ageing, further aggravated by the lack of services and of economic opportunities (local jobs), resulting in a vicious circle. Due to depopulation - especially young and/or highly educated people leaving ‘for good’ and related ‘brain drain’ - in many rural communities (especially in poorer parts of Europe) the more disadvantaged groups of inhabitants stay behind, resulting small communities having significant capacity constraints. These limitations are evident in various areas, including strategic planning, generating new project ideas, implementing initiatives and projects, accessing public funding, and engaging in exchanges with other communities. Partly due to this lack of capacity and appropriate interest representation, public – including EU – funding fails to reach the local level and/or those most in need.

EU funding holds a strong potential both in terms of addressing specific rural challenges (such as the lack of services) and in terms of building capacity of rural communities. In particular, it is widely acknowledged that bottom-up, community-led local development (CLLD) approaches – such as LEADER and Smart Villages - are highly effective in addressing not only local challenges, such as rural depopulation and service deficiencies, but also global issues, such as climate change. In particular, rural areas are (or should be) at the heart of the green transition, as most of the climate crisis issues (such as restoration of (fresh)water and other ecosystems, C sequestration, green transformation of agriculture) have to be addressed in rural areas for the benefit of the whole society. Supporting rural areas and people in these efforts are critical.

In addition to LEADER that has proved to be a highly successful method for distributing funds locally and targeting the real needs of rural communities, the EU’s Smart Villages concept offers a crucial support mechanism at the very local rural community level. Smart Villages, introduced as a policy concept during the 2021-2027 period, has strong potential to become an effective tool for engaging local rural communities and stakeholders. This concept not only complements but also revitalises the LEADER approach by extending its principles - such as strategic planning and participatory methods - directly to the local community level, while placing an even greater emphasis on social and technological innovation. As the LTVRA report highlights “[s]upport for ‘smart villages’ within and outside LEADER is expected to contribute to unlock the potential of digital, social and technological innovation in rural areas”.

However, during the past and current programming periods, the potential of EU policies and CLLD has not been fully exploited. Rural development, and especially community-driven territorial approaches, are currently underemphasised and underfunded within the existing Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP is predominantly influenced by agricultural (sectoral) interests, a considerable proportion of direct payments going to very large farms[2] – sometimes even to those with production methods that are neither good for the environment nor for society[3].

CLLD approaches have consistently received minimal funding across successive programming periods. As the LTVRA Report highlights the absolute amount assigned to LEADER did not increase compared to the previous period, and “LEADER is expected to do more with less”.

The introduction of the Smart Villages approach brings new opportunities. However, for the time being Smart Villages has been incorporated into the CAP beyond the LEADER approach in only a few Member States , and has not been included under the Cohesion Policy programmes, despite its original conception as a multi-funded initiative[4].

The multi-funded Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) approach, or even the CLLD approach under other funds, has not gained widespread adoption despite extensive encouragement and advocacy from the European Commission. Notably, countries (Sweden, Portugal and Slovakia) that experimented with cohesion policy-funded element of CLLD, have abandoned this approach post-2023.[5] Multi-funding in CLLD has been considered challenging (e.g. due to the administrative burden and harmonisation of funds).[6]

The Cohesion Policy also does not provide adequate support for rural areas. While there is some evidence that Cohesion Policy programmes target rural areas, there is lack of focused targeting of available support, as evidenced also by the fact that 79% of Cohesion Policy funds are not even territorially tagged, leaving it unclear whether rural areas are being supported. A recent study on Cohesion Policy (Nils Redeker et als., 2024) argued that “The [Cohesion Policy] funds frequently target places that are not particularly needy and mainly benefit people at the upper end of the income distribution. Cohesion policy thus requires root-and-branch reform. This includes sharper focus on truly disadvantaged areas, a more precise definition of local economic challenges, improved funding access for small municipalities and companies, and redirection of resources now allocated to wealthy member states towards an EU-level investment instrument.”

Consequently, rural communities often feel that their needs and interests are overlooked at the national, regional, and sometimes even municipal levels, as territorial and regional programmes tend to favour more densely populated urban areas and cities. The fact that the lack of sufficient and appropriate support to rural areas and communities have persisted over several programming periods, highlights that ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option if we want to improve the situation of rural areas.

There is need for a more profound change in how Member States are incentivised or ‘compelled’ to take support for rural areas more seriously. Regardless of the future Rural Development Policy approach chosen by the European Commission, it is essential to mandate that Member States allocate sufficient funds to rural development, with a particular emphasis on community-led territorial models.

While the flexibility afforded to Member States under the shared management system, allowing them to adapt their programmes to national needs, has been appreciated, it has proven insufficient — except in rare cases — in ensuring that Member States prioritise rural areas and effectively resource local rural development interventions. When questioned about the shortcomings in rural development focus and the use of CLLD in EU funds and programmes, the European Commission often cites the ‘shared management system,’ emphasising that Member States are responsible for how they use EU funds within the broader EU framework. However, soft EU recommendations and the existing regulatory framework (such as the minimum 5% allocation for LEADER) are no longer sufficient. The EU must adopt a more proactive approach, implementing rules and regulations that require better harmonisation of the use of funds and ensure stronger support for rural areas. For instance a recent study by the European Commission on LEADER[7] suggests that a “[m]ore extensive use of lead fund options, the harmonisation of the various procedures that still exist for the different ESI funds, or even a common regulation and national legal framework for all funds could be explored.”

Furthermore, programmes under direct management also tend to benefit the strongest players. Due to the design of the programme (i.e. focus on research & innovation), Horizon projects – even those explicitly targeting rural communities – are targeted at large institutions (consultancies, research institutes, universities, etc.), also with the capacity and knowledge to apply successfully. Rural communities are only indirect (if at all) beneficiaries of these projects. For instance, Horizon Europe statistics show that 90% of Horizon Europe funds has benefitted directly higher education institutes (34%), private for-profit entities (29%) and research organisations (27%), and 10% of funds have directly benefitted public bodies and other types of stakeholders.[8]

The proposed Rural Development Policy models

In the context of policies and programmes under ‘shared management’, we see two options to take a more committed action at the European and national levels towards rural development:

Option 1: A dedicated Rural Development Policy with its own EU fund and national (and regional) rural development programmes;

Option 2: The compulsory Rural Pact Model in the design and implementation of a dedicated Rural Development Strategy with allocations from current programmes and funds (multi-fund approach).

At the heart of both models is an independent European Rural Development Policy and Strategy (based on the LTVRA and the Rural Pact) implemented through national / regional Rural Development Strategies and/or programmes.[9]

A dedicated Rural Development Policy and Fund

Introducing a dedicated Rural Development Policy & fund, along with corresponding programmes, could be one of the approaches to address several of the challenges currently facing rural areas. This approach would ensure that rural issues receive greater attention and more substantial funding. A dedicated Rural Development Policy and associated programmes in Member States would also promote a more holistic and integrated approach to rural development.

An independent funding for this new policy (European Rural Development Fund – ERUDF) should be established while negotiating the post-2027 regulations. ERUDF would mean reducing current EAFRD and Cohesion Policy funds (ERDF, ESF, etc.) funds, to allocate resources to the new fund. It is essential that the Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) approach - encompassing initiatives like LEADER and Smart Villages - plays an even more central role in such a new policy, with a significantly larger relative and absolute allocation of funds than what is currently available under LEADER and Smart Villages.

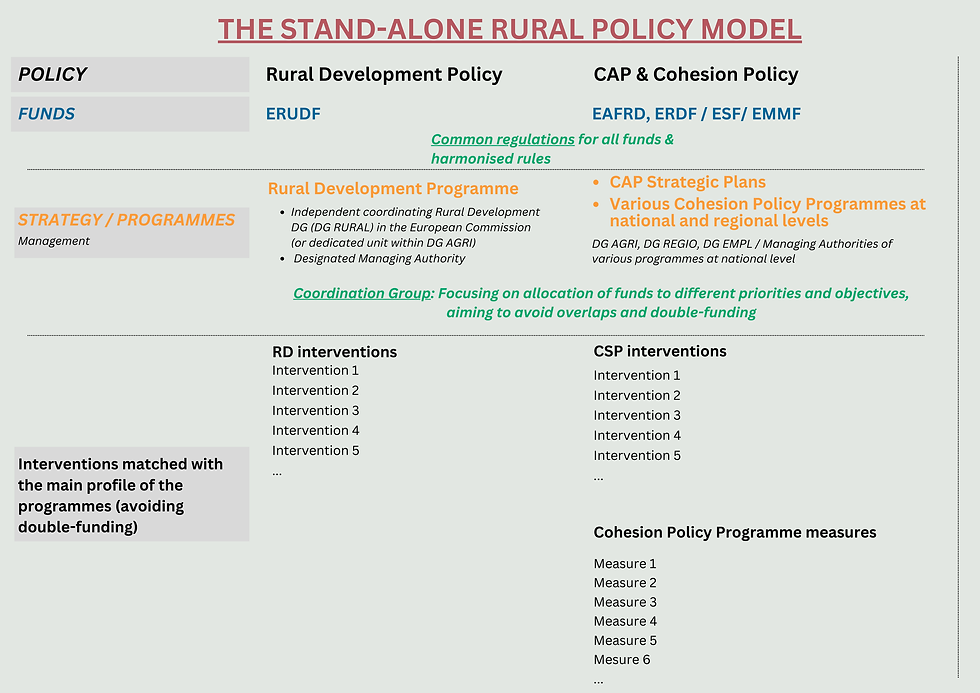

Figure 1: The stand-alone Rural Development Policy model

Source: E40

However, creating an independent Rural Development Policy also presents risks, such as complicating EU fund management and making the harmonisation of various funds more challenging, unless a common regulation and national legal framework for all funds is being considered. For example, it may become difficult to clearly demarcate funds, distinguishing between purely agricultural interventions and those focused on rural development, such as short supply chains. Additionally, there is a risk that funding allocated to rural development could be reduced during negotiations with other, more influential sectoral and territorial interests, unless there is a minimum allocation to the new rural development programme (of all relevant EU funds). Finally, it can be argued that rural aspects should be filtering through all policies as a horizontal dimension (rather than constitute a stand-alone policy), aligned with the 'rural proofing' concept.

"On the issue of whether there should be a dedicated rural policy fund, my concern is that you know we've believed that rural proofing has to be successful. It is not currently successful, but the concept that society generally believes in the importance of rural areas and believes in the importance of linking rural and urban together means that all departments of government at EU and at national level should buy into that concept. If they don't do that, if education and transport and technology departments don't have allocations for rural policies, then the whole concept of rural proofing will have failed, and I'm not ready yet to allow either the Commission or governments to walk away from having said some nice words about rural proofing, but not actually able to demonstrate that they have made that commitment." (Tom Jones, ERCA, at the SVN meeting in reflection on the draft declaration)

The compulsory Rural Pact Model

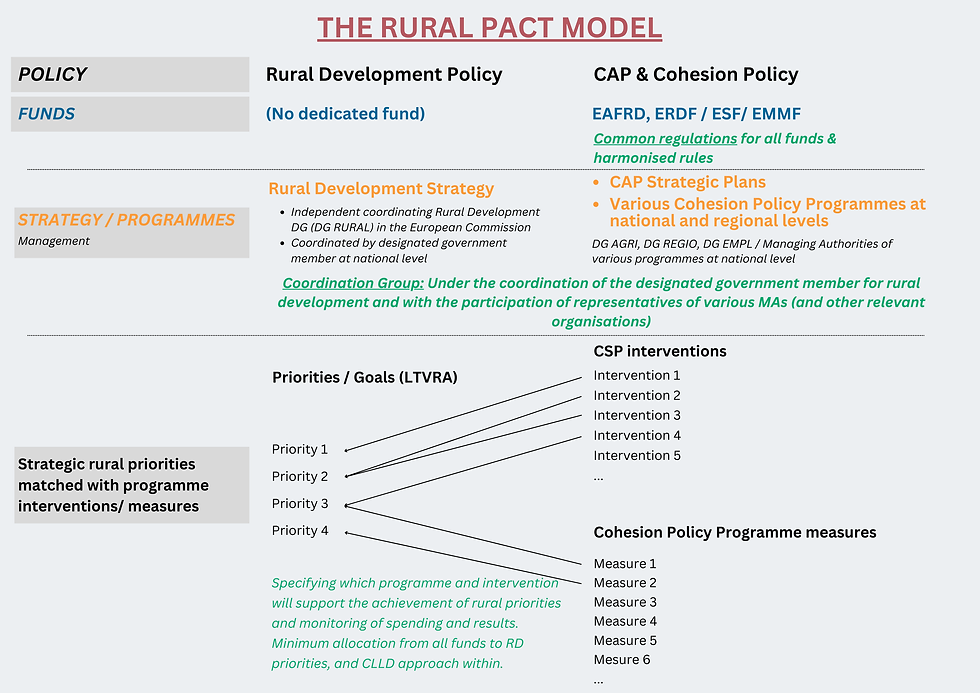

The (compulsory) Rural Pact Model could offer a crucial option for the reform of future rural development policies. Under the proposed Rural Pact Model – similarly to the dedicated Rural Development Policy & Fund Model – the European Commission should require Member States to develop national/ regional Rural Development Policies and Strategies, which should align with the priorities established in the Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas (LTVRA). However, contrary to the Rural Development Policy Model, the Rural Development Strategy would not have its new independent funding but funding would be drawn from CAP (EAFRD) and Cohesion Policy (ERDF, ESF, etc.) funding. The European Commission would define a compulsory minimum percentage of existing CAP and Cohesion Policy funds that should be allocated for the Rural Development Strategies goals.

For example, the Commission could require that at least 30-40% of EU (CAP and Cohesion Policy) funding be dedicated to broader rural development goals and rural areas, beyond those supporting the agricultural sector, with at least 10% distributed through Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) methods, such as LEADER and Smart Villages. This would neccesitate the sectoral tagging (agriculture vs. wider rural development goals) of CAP funds (especially EAFRD) and the territorial tagging (urban, peri-urban vs. rural) of Cohesion Policy funds. When defining rural target areas, the rural-urban classification of local level administrative units - rather than higher regional level classification - should be used (as the latter risks that funds ending up supporting wealthy areas within less developed regions).

While the share of overall EU funds allocated to rural development goals / rural areas would be compulsory, there would be flexibility on how Member States finance specific objectives of their Rural Development Strategies using a wide array of funding sources and programmes.

Member States would also be required to establish certain institutional mechanisms for programme design and decisions on fund allocation, without which they would be ineligible for the relevant share of EU funds. The guidance provided in the Rural Pact Support Office (RPSO) publication, “Making the Rural Pact Happen in Member States” (2023), could serve as a strong foundation for setting these institutional conditions. These conditions include: (1) appointing a designated government member and establishing inter-sectoral and inter-ministerial coordination groups to define Rural Development Strategies at national and regional levels; (2) creating structures and mechanisms to engage with rural communities in both the design and implementation of rural strategies; and (3) providing capacity-building and networking support. For the latter, National Rural Networks – concerned with both the CAP and the Cohesion Policy – should support the implementation of the Rural Development Strategies, bringing together stakeholders concerned with various programmes and EU funds.

The institutional structure required at the national level should be mirrored at the European level. For instance there is likely to be a need for a designated DG within the European Commission for Rural Development (DG RURAL) or as minimum a dedicated unit within DG AGRI, responsible for the coordination with other DGs. European networking should be ensured across funds, by a dedicated horizontal European Network for Rural Development (rather than CAP Network). These institutional structures and mechanisms would be responsible for designing and implementing Rural Development Strategies aligned with the key priority areas of the LTVRA. They would also define the measures and interventions of various programmes, including the CAP Strategic Plans and Cohesion Policy programmes, that will support the implementation of the Rural Development Strategy(s) and ensure compliance with the required minimum funding allocations.

It is important to note that the Rural Pact Model can only work effectively if it is compulsory for Member States (set by regulation) and set as a condition to accessing funds. If Member States have the possibility not to opt for such a model (i.e. it remains at the level of recommendations), it is likely that only limited efforts will be made across Europe just as in previous programming periods. In case the Rural Pact Model (and Rural Development Strategy) is not compulsory, then the dedicated Rural Development Policy & Fund (Option 1) is likely to ensure more suitable rural development model.

Figure 2: The Rural Pact model

Source: E40

Beside the programmes under ‘shared management’, small rural communities should also directly benefit from EU programmes under ‘direct management’. Public stakeholders, local communities and local NGOs are the main enablers and depositories of local (rural) innovation and therefore, could be better targeted directly – coupled with capacity-building – by Horizon and other relevant EU programmes. Larger community networks or organisations (such as the Smart Village Network and other similar organisations) should be enabled to support smaller communities in their efforts to apply and act as direct partners (not only demonstration sites) in Horizon Europe and other similar projects. For instance, making rural communities direct partners and building their capacity in projects could become a compulsory requirement for larger applicant organisations and networks when applying for Horizon funds.

Helping communities to better benefit from EU funds & programmes

Small rural communities need to receive technical capacity-building/ training and financial support to embrace strategic thinking with a focus on innovation, to develop project ideas and apply for available funding. This support can be provided for instance by LEADER LAGs at the local level, National Rural Networks at the national level, and dedicated European projects and networks at European level (e.g. projects like the EU-funded Preparatory Actions on Smart Rural Areas, the ENRD, the Rural Pact Support Office or through supporting the efforts of EU-wide stakeholder networks such as the Smart Village Network).

Financial and technical support to innovative project ideas should already start from the identification of ideas and examples, and planning phase (not only the project implementation and financing phase). International exchange targeted at small rural communities can largely help generate ideas locally. Furthermore, rural communities need technical support from various networks to help them participate in EU-wide calls and projects as direct partners. Specific conditions and support need to be provided so that less powerful (rural) stakeholders do not need to compete (e.g. as far as co-financing requirements or capacity to deal with administrative burdens are concerned) with much more powerful 'players'.

The Smart Rural 21 project 2020-2022 (Preparatory Action for Smart Rural Areas) – funded by the European Commission - created a model of support at various stages working directly with small rural communities: including identification of open-minded communities, support for strategy development, help generating project ideas, financially support innovative projects, and enable exchange among communities.

Overall, the local rural community level (through organisations that credibly represent rural communities, including local public authorities, village associations and other NGOs) should become a key target and direct beneficiaries of rural development support. Support should focus on a holistic approach at the local level, i.e. not just individual projects, but projects that are part of integrated, longer term, strategic thinking.

Making the new model(s) happen - Changing business as usual

The planning of the regulatory framework of the new EU delivery model of rural development policies post-2027 starts at the European level. The Long Term Vision for Rural Areas and the Rural Pact demonstrate a strong political commitment towards a more integrated rural development policy of the future. The consultation on the future rural development policy is highly appreciated.

EU institutions have to stand up more firmly for the LTRVA priorities of stronger, more resilient, more prosperous and more connected rural areas and Rural Pact goal for stronger engagement of rural communities and must reinforce the dedicated use of EU funds amid the competing, more powerful interests.

The European Commission should show strong commitment towards Member States to translate the LTVRA and the Rural Pact into tangible policies and regulations, ensuring a solid financial framework for rural areas and communities. We are already late in acting to save rural communities and to tackle climate change effectively. Rural areas are places where the most can be done to mitigate and adapt to the consequences of climate change. Therefore, rural areas and communities need to be supported not only for their own survival, but the survival of all of us. Business as usual and a soft approach of providing tools and recommendations on how Member States might use available funds and tools will no longer be enough to reverse the negative trends in rural areas and the negative impacts of climate change.

[1] A key phylosophy presented also in the publication Rural Europe takes Action: no more business as usual (ARC2020 and Forum Synergies, 2022)

[2] A publication of the EU on Direct payments to agricultural producers (Financial year 2021: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/direct-aid-report-2021_en.pdf) showed that while farms over 250 ha constitute 1.1% of all beneficiaries they received 22.1% of the direct payments, the same figure for farms between 5 to 250 ha that consituted 50% of beneficiaries is 72.1%, while farms that are less than 5 ha consituted 48.9% of beneficiaries they only received 5.8% of the direct payments.

[3] See for instance Murray W. Scown et al.s (2020): Billions in Misspent EU Agricultural Subsidies Could Support the Sustainable Development Goals. The study found that at the time out of the €60 bilion a year that CAP paid in subsidies to support farmers’ income, at least €24 billion a year went “to support incomes in the richest farming regions of the EU with the fewest farm jobs. Meanwile, the poorest regions with the most farm jobs [were] left behind.” (ARC2020, 3 Sept 2020: https://www.arc2020.eu/eu-subsidies-benefit-big-farms-while-underfunding-greener-and-poorer-plots-new-research/)

[4] See Factsheets produced by the Smart Rural 27 project on Smart Villages: https://www.smartrural27.eu/cap-analysis/

[5] See Kah et al. (2023): CLLD in the 2014–2020 EU Programming Period: An Innovative Framework for Local Development, World (2023), 4(1): https://www.mdpi.com/2673-4060/4/1/9

[6] “[T]he multi-fund approach was seen as more complex to implement than mono-fund approach, despite attempts to simplify. […] Even though other funds than EAFRD increased the LAGs’ opportunities to cover broader social and economic issues through additional funds, most Member States and regions decided to use mono-fund schemes for LEADER.” (EC, 2024: Evaluation of the impact of LEADER towards the general objective "balanced territorial development”: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=SWD(2024)170&lang=en)

[7] EC (2024). Evaluation of the impact of LEADER towards the general objective "balanced territorial development"

[8] Horizon Europe implementation Key data 2021-2023 https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/311df01e-215f-11ef-a251-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[9] Furthermore, the future EU Rural Development Policy would build on the vertical integration of rural development strategies. The EU would provide the overall framework and goals – already set out in the LTVRA and the future Rural Development Policy, including the four priority areas. Member States (or regions in case of regionalised Member States) would design their own Rural Development Strategies. Rural Development Strategies will be rolled out at all levels - regions, municipalities, and local rural communities - by requiring national governments to allocate funding also to integrated regional, municipal, and local rural strategies (including smart village strategies and LEADER Local Development Strategies) that are aligned with the national Rural Development Strategy. LEADER LDSs and Smart Villages strategies could be supported through dedicated CLLD interventions and related lumpsum funding (like it is currently in LEADER) that would cover small-scale projects. Larger (e.g. infrastructural) projects planned within the local strategies would be supported from other relevant interventions. When beneficiaries managing local development (LEADER and Smart Villages) strategies apply with projects under other interventions, these applications could receive extra scores due to being part of an integrated local rural strategy.

Comments